Kansas is one of 33 states which have the death penalty; 17 states and the District of Columbia do not. The federal government, both civilian and military, also allows for capital punishment.

This is the third time that Kansas has enacted a death penalty statute.

- The state’s first death penalty law was abolished by the legislature on January 30, 1907; for that reason, January 30 is celebrated by KCADP as Abolition Day in Kansas.

- The state had no death penalty until 1935, when a new statute became law. According to Truman Capote, who chronicled the murder of a Kansas family in his 1966 book, In Cold Blood, the legislature’s vote to restore the death penalty in 1935 was partially attributed to the “sudden prevalence in the Midwest of rampaging professional criminals” such as Alvin “Old Creepy” Karpas, Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd, and Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker.

- There were no executions under the 1935 law until 1944. The hangman took nine lives during the next 10 years.

- For six years, from 1954 to 1960, there were no hangings in Kansas except at the Army and Air Force Disciplinary Barracks. George Docking, Governor of the state from 1957 to 1960, was responsible for this hiatus. He was opposed to the death penalty, saying “I just don’t like killing people.”

- When Docking was defeated for re-election in 1960, in part because of his attitude towards capital punishment, there were five men on death row at Lansing. Before he left office in January 1961, Docking commuted the sentences of two of the men, Earl Wilson and Bobby Joe Spencer, to life in prison. The remaining three were Lowell Lee Andrews, who was executed on November 30, 1962, and Richard Hickock and Perry Smith, the infamous killers of the Clutter family, who were both hanged on April 14, 1965. The last executions in Kansas took place on June 22, 1965, when the state hanged George Ronald York and James Douglas Latham for the 1961 murder of a Kansas railroad worker. The two young soldiers—York was 18 and Latham was 19 at the time of their crime—had embarked on a cross-country killing spree after their escape from the stockade at Fort Hood where both had been imprisoned for going AWOL.

- On June 29, 1972, the United States Supreme Court, in the Furman vs. Georgia decision, struck down the death penalty because it could not agree on how the punishment could be carried our fairly and humanely. That case voided death penalty laws in 40 states, including Kansas, and commuted the sentences of 629 individuals on death rows.

- In the 1976 Gregg v. Georgia ruling, the Court said that the death penalty per se was not unconstitutional and allowed states to reinstate capital punishment if they followed certain procedural reforms including a two-phase trial and automatic appeals. Litigation since the penalty was reinstated has continued to raise significant issues about the fairness of its application. There were no executions in the United States from 1968 until 1977, when Gary Gilmore’s death by firing squad ended the moratorium.

- It took Kansas 18 years to enact a new death penalty law, which was passed on April 23, 1994. Then-governor Joan Finney neither vetoed nor signed the bill.

- The current law took effect July 1, 1994.

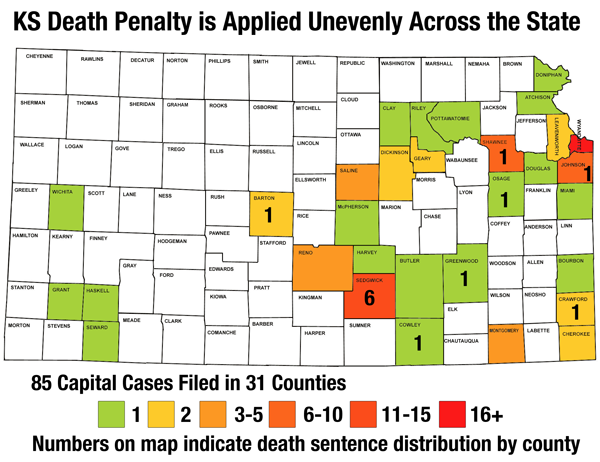

Since 1994 there have been more than 100 potential capital cases in Kansas; capital charges were filed in 85 cases in 31 counties.

Top Four Counties: Wyandotte (20), Sedgwick (12 ), Johnson (7), Shawnee (5)

The rest: Atchison (1), Barton (2), Bourbon (1), Butler (1), Cherokee (2), Clay (1), Cowley (1), Crawford (2), Dickinson (2), Doniphan (1), Douglas (1), Geary (2), Grant (1), Greenwood (1), Harvey (1), Haskell (1), Leavenworth (2), McPherson (1), Miami (1), Montgomery (3), Osage (1), Pottawatomie (1), Reno (4), Riley (1), Saline (3), Seward (1), Wichita (1)

Thirteen men have been sentenced to death; one had the death sentence removed at the request of the District Attorney, two have had their sentences vacated by the Kansas Supreme Court, and the others remain in early appeals. There have been no executions.

There have been 26 capital trials since 1994. Death sentences were handed out in thirteen of those cases (see the list on the Death Row page). Thirteen men who were tried were not sentenced to death after trial for capital murder. They are:

- Robert Verge in the deaths of Kyle and Chrystine Moore, tried in Dickinson County. Sentence: Life sentence with eligibility for parole after 40 years, plus 19 year sentence for other charges.

- Virgil Bradford in the deaths of Kyle and Chrystine Moore, tried in Dickinson County. Sentence: Life sentence with eligibility for parole after 40 years.

- Frank Delterman in the death of Patrick Livingston, Cherokee County. Sentence: Life sentence with eligibility for parole after 40 years (prosecution didn’t seek death in the penalty phase).

- Richard Powell in the deaths of Mark and Melvin Mims, tried in Wyandotte County. In the penalty phase, the Court ruled him mentally retarded so the case then proceeded with non-capital sentencing.

- Gordon Martis, convicted of first-degree murder of Alphonse Moore, second-degree murder of Jerry Seals, tried in Wyandotte County.

- Jeffrey Hebert in the death of James Kenney, tried in Clay County. Sentence: Life sentence with eligibility for parole after 50 years, plus 65 months for other charges.

- Cornelius Oliver, convicted of two premeditated first-degree and two felony first-degree murders in the deaths of Jermaine Levy, Quincy Williams, Dessa Ford, and Raeshawnda Wheaton, tried in Sedgwick County. Sentence: Four life sentences with eligibility for parole after 50 years on two counts and 20-years on two counts. Codefendant Bell was acquitted on four counts of murder.

- Christopher Trotter in the deaths of Traylenea Huff and James Darnell Wallace, tried in Wyandotte County. Sentence: Life with parole eligibility after 50 years.

- Darrell Stallings, convicted in the deaths of Tameika Jackson, Melvin Montague, Samantha Sigler, Destiny Wiles, and Trina Jennings, tried in Wyandotte County. Sentence: Five life sentences with parole eligibility after 50 years on each sentence.

- Greg Moore in the death of Kurt Ford, tried in Harvey County. Sentence: Life in prison without parole.

- Ted Burnett in the death of Chelsea Brooks in 2006, tried in Sedgwick County. Sentence: Life in prison without parole.

- Elgin Robinson in the death Chelsea Brooks in 2006, tried in Sedgwick County. Sentence: Life in prison without parole.

- Nathaniel Hill in the deaths of April Milholland and Samuel Yanofsky in 2003, tried in Montgomery County. Sentence:Life sentence with eligibility for parole after 50 years, plus additional time for drug crimes. (State withdrew the notice to seek death)

Can mistakes happen in capital cases?

- In January 1998, Gentry Bolton was charged in Wyandotte County on two counts of capital murder following homicides during two convenience store robberies. The two robbery/homicides were said to be part of a “common scheme” thus making them eligible to be considered as capital crimes. At Bolton’s preliminary hearing May 12, it was revealed that police did not follow up fully on a December 31 call to the TIPS Hotline from a woman who had witnessed one of the shootings. The woman subsequently gave police a full statement about the shooting in March, but police did not follow up on her information. Less than a week before the preliminary hearing, prosecutors told Bolton’s attorneys that testing indicated that different weapons had been used at the two homicides. On May 20, prosecutors dropped the capital murder charge in that case and amended the other to a first-degree murder charge.

- In 1995, Stephen Shively was charged with capital murder in the killing of a Topeka policeman. Although emotions were high because of the death of a law enforcement officer, the judge ruled that premeditation did not exist, so Shively was bound over on a charge of intentional second degree murder.

- Around the nation, more than 100 individuals have been released from death rows on grounds of innocence. (See The Nation)

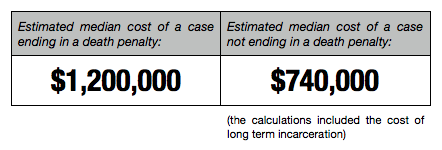

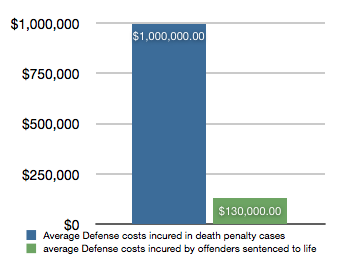

What is the cost of the death penalty?

It is hard to determine the total cost of a death penalty in Kansas. Expenses are incurred by both state and local government. While some individual costs are known, such as the budget appropriations for the Death Penalty Defense Unit, other costs such as local and state prosecution and court expenses are not itemized.

- Death cases are more costly from the very beginning. Pre-trial handling is different, trials are longer, and a separate sentencing phase is held. For example, in both the Marsh and Kleypas cases, 500 jurors were summoned each time, and all were paid mileage and the $10 daily fee.

- In mid-July 1997, Saline County Attorney Julie McKenna told County Commissioners that if she exceeded her budget, it would be because of the capital murder prosecution of Allan White. At midway in the fiscal year, travel was already over budget and 72% of witness fees had been spent.

- In March 2001, the Board of Indigents Defense reported that four current cases have strained its budget and the Board may have to ask the Legislature for a supplement to its $1.4 million budget for death penalty cases. The complexity of the current cases, involving multiple victims, multiple crime scenes or multiple defendants, makes these cases particularly expensive to defend.

- The defense of Gary Kleypas cost $188,000. The defense of Stanley Elms, cost $259,000.

- So far, Kansas taxpayers have spent $771,240 convicting John E. Robinson, Sr. The Kansas Board of Indigents’ Defense Services spent $569,862 defending Reginald Car and $566,111 defending his brother Jonathan. These three cases depleted the board’s funds fordeath penalty cases during this fiscal year, which ends June 30, 2003. In November 2002 the board asked for an emergency allocation of $600,000 from the state budget office. Because defense services are constitutionally required, the board is exempt from the state budget cuts that are currently being made.

Information from other states indicates that the death penalty costs more than prison. A 1997 study in Nebraska concluded that “adjudication of capital cases incurs additional costs that are significantly greater than the savings in incarceration costs realized from execution as opposed to life imprisonment.” A former Texas Attorney General stated that it cost three times as much to carry out a death sentence as it did to imprison for forty years. The Savannah, Georgia, Morning News reported in January 2001 that small counties in Georgia are going broke prosecuting death penalty cases. “If you’re spending $300,000 for a [death penalty] case, that’s $300,000 that could be used for buying road equipment, paying salaries, or the fire and sheriff’s departments,” said Richard Douglas, Administrator of Long County, Georgia.

What about victims’ families and their needs?

In Kansas, victims’ families have testified both in support and opposition to a death penalty. No matter their view on the death penalty, they all want the public to be protected from murderers. The problem with the death penalty is that it isn’t utilized until someone is already dead. As the father of one victim said about the loss of his child, “…nothing you do will give her back to our family.” Prolonged appeals required by Supreme Court rulings mean that families of murder victims do not know the final disposition for many years, and have to relive the experience at each new trial.

Some victims’ families have joined together in an organization called Murder Victims Families for Reconciliation. For information about MVFR, in Kansas contact 785-232-5958, mvfrks@cox.net. You can read statements from murder victim family members on our victim voices page.